HRNM Volunteer

The Hampton Roads Naval Museum displays a boat company builder’s plate and an American flag with bullet holes in its exhibit, “The Ten Thousand-Day War at Sea: The U.S. Navy in Vietnam.” These artifacts, talismans of a war fought fifty years ago, demonstrate the contributions of the riverine Sailors in Vietnam. Crews of the fast-moving river boats interdicted transfer of Viet Cong war supplies and personnel. Concurrently, they improved the health, welfare, and safety of innocent civilians in their area of operational responsibility.[i] They carried out these duties admirably, enduring lengthy repeated patrols which were generally tedious but could be interspersed with moments of terror and stress.[ii]

|

| Unit patch of Task Force 116, The River Patrol Force, South Vietnam, 1967 (Courtesy of Larry Weatherall) |

By the summer of 1965, it seemed clear that South Vietnamese Navy (VNN) forces would be unable to control the waterways of the Mekong River Delta or the Rung Sat Special Zone (RSSZ).[iii] This yielded a new objective: “for the U.S. Navy to develop a plan to cover 500 miles of major waterways to check day traffic and establish a delta wide curfew at night.” The result was the December 18, 1965, establishment of Task Force 116 (River Patrol Force) in Operation Game Warden.[iv]

The goal of U.S. Navy involvement in riverine operations was to supplement the offshore interdiction of insurgents and their supplies and equipment by clearing the Viet Cong (VC) from havens from which they could attack South Vietnamese cities, impose taxes on inhabitants, and terrorize innocent civilians in a rich, fertile land that produced the most rice in the country. An early measure, using propeller-driven 36-foot LCPLs initiated by Rear Admiral Norvell G. Ward, was ineffective because of slow speed of the craft and lack of protection from Viet Cong fire. The fiberglass PBR emerged. Its two 216 horsepower diesel engines powered a water jet propulsion system, and it was equipped with a Raytheon pathfinder radar set and provided armor around the Boat Captain (Coxswain’s) operating position. It could operate in nearly all inland waters. It responded with alacrity to even slight manipulation of the helm and did not rust. Apart from problems removing flotsam from the water jets and at times removing snakes, it was simple to operate and maintain.[v] PBRs were armed with twin .50 caliber machine guns forward and a single aft and an M60 machine gun amidships. There was a grenade launcher, 4 M16 small arms, and a .45 caliber pistol carried by the Boat Captain.

The goal of U.S. Navy involvement in riverine operations was to supplement the offshore interdiction of insurgents and their supplies and equipment by clearing the Viet Cong (VC) from havens from which they could attack South Vietnamese cities, impose taxes on inhabitants, and terrorize innocent civilians in a rich, fertile land that produced the most rice in the country. An early measure, using propeller-driven 36-foot LCPLs initiated by Rear Admiral Norvell G. Ward, was ineffective because of slow speed of the craft and lack of protection from Viet Cong fire. The fiberglass PBR emerged. Its two 216 horsepower diesel engines powered a water jet propulsion system, and it was equipped with a Raytheon pathfinder radar set and provided armor around the Boat Captain (Coxswain’s) operating position. It could operate in nearly all inland waters. It responded with alacrity to even slight manipulation of the helm and did not rust. Apart from problems removing flotsam from the water jets and at times removing snakes, it was simple to operate and maintain.[v] PBRs were armed with twin .50 caliber machine guns forward and a single aft and an M60 machine gun amidships. There was a grenade launcher, 4 M16 small arms, and a .45 caliber pistol carried by the Boat Captain.

Crewing a PBR required a First Class Petty Officer, usually drawn from a deck rate such as Boatswain’s Mate, Quartermaster, or Signalman to serve as Boat Captain; a Gunner’s Mate Third Class; an Engineman Third Class; and an ordinary seaman. If petty officers were unavailable, strikers might be used. Sometimes, a Vietnamese police officer or interpreter might be assigned. The crews were cross-trained. All hands learned how to operate, how “to drive the boat, how to clean weapons and break them down.” Operation and maintenance of the boat’s engines and steering gear was the responsibility of the Engineman or Engineman striker. River sections, later called “divisions,” each consisted of ten PBRs under the command of a U.S. Navy lieutenant and contained 42 enlisted personnel.

PBR operations were carried out to remove Viet Cong influence from the Mekong River delta and contiguous areas by aggressive daylight and night patrols, each consisting of two to three PBRs. Patrols were an exhausting 10 hours in length, excluding transit time to the area under surveillance. In June 1967, the Navy made 639 daylight patrols and 701 at night. As a result, the PBR crews detained 84 individuals and seized 25 surface craft.[vi] Boat captains cruised along inland rivers and inlets from which VC forces emerged to extort “taxes” and otherwise harry indigenous craft and their operators engaged in innocent passage. In the daytime, PBR crews stopped and made fast to the craft being searched, inspecting all river craft traffic to establish the identity and bona fides of its operators. Crews removed suspected VC insurgents and transferred any contraband to the closest South Vietnamese police activity or VNN installation. The effort could be tedious, though in some cases PBRs were taken under sniper fire from VC hideouts ashore without crew members being able to identify its source. The bullet-riddled flag on display from PBR 109 was discovered at the end of its patrol. No patrols were routine and hostilities could emerge without warning.[vii] At the end of each patrol, the craft was cleaned of debris, rearmed, and refueled for the next patrol.

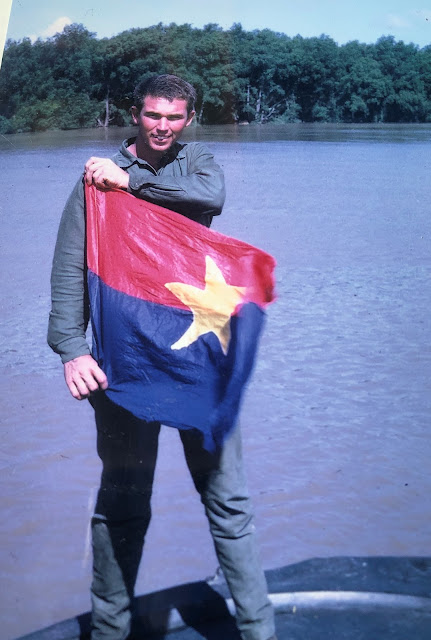

|

| GMSN David A. Wilkinson displays a VC flag he seized from a captured VC watercraft in the Ham Luong River. (Courtesy of Larry Weatherall) |

Night evolutions were different because traffic on the rivers was forbidden, and craft sighted were presumed hostile. In some cases, boat captains shut down engines and drifted with radar energized and starlight scopes in use, hopeful that they might detect illicit camps and traffic and destroy it. This was not foolproof, and in one case glowing light was found to be fireflies. On October 31, 1966, Boat Captain Boatswain’s Mate First Class James E. Williams and the crew of PBR 105 discovered a large concentration of VC insurgents attempting to cross the Mekong River about 10 miles west of My Tho. He began an attack at dusk which continued into full darkness. In addition to pressing the attack in his boat, he requested and received assistance from HAL-3 (Helicopter Attack Light Squadron Three). These Sailors and aviators stopped the crossing, destroyed multiple VC watercraft, and killed a large number of insurgents. Williams earned the Medal of Honor for this action. A key feature of his performance and that of all PBR boat captains and patrol officers was the necessity of making tactical and weapons employment decisions rapidly under duress. Very few commanding officers of Seventh Fleet ships could do that. This combat regimen continued day in and day out until individual personnel were rotated out of theater, medically evacuated, or killed. It was, as Captain Thomas Glickman observed, “a strange way to fight a war.”[viii]

The PBR crews faced certain hazards. One great danger emerged because VNN shore bases were infiltrated by VC insurgents.[ix] By June 1967, it was reported that, “Viet Cong were keeping detailed records on the movements and habits of various PBRs in an attempt to discern patrol patterns that could be used in planning ambushes.” For that reason, “external hull numbers and identifying marks were removed from all PBRs.” Were it not for that order, the builder’s plate for PBR 105 might never have come to the Hampton Roads Naval Museum.

The PBR crews faced certain hazards. One great danger emerged because VNN shore bases were infiltrated by VC insurgents.[ix] By June 1967, it was reported that, “Viet Cong were keeping detailed records on the movements and habits of various PBRs in an attempt to discern patrol patterns that could be used in planning ambushes.” For that reason, “external hull numbers and identifying marks were removed from all PBRs.” Were it not for that order, the builder’s plate for PBR 105 might never have come to the Hampton Roads Naval Museum.

|

| PBRs moored alongside USS Harnett County (LST 821). There are no hull numbers on the craft, to counter VC efforts to hinder PBR operations. (Courtesy of Larry Weatherall) |

The flag and builder’s plate on display at the naval museum are thus a powerful and lasting tribute to those who served so ably and well in the service of the United States Navy on a hostile foreign shore. They did so despite a deeply divided national view of the Vietnam War.

Author’s Note: Many thanks to Larry Weatherall and David Wilkinson for their help with this post.

[i] “Boy’s Harelip Corrected Through Navymen’s Help, Jackstaff, Naval Forces Vietnam, May 19, 1967, 4, which shows a photograph of Lieutenant Charles D. Witt and the 14 year old boy whose deformity was completely corrected; “Navy Surgical Team,” Jackstaff, JOC Ted Jorgenson, Naval Forces Vietnam, June 30, 1967, 4; See Also COMNAVFORVN Ltr FF-5/03:gem, 5750, Serial 0603 of 9 August 1967, which reports the May 24th, 1967 death of Lieutenant Witt in an ambush and other matters to include Operational Tempo (OPTEMPO).

[ii] Interview with former Engineman Second Class James Lawrence “Larry” Weatherall, USN, at Joint Base Little Creek/Fort Story, November 9, 2021. Larry Weatherall has been instrumental in restoring the PBR on static display at Joint Base Little Creek/Fort Story.

[iii] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 91-3.

[iv] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 95-6.

[v] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 104-110.

[vi] Monthly Historical Supplement (June 1967), U.S. Naval Forces Vietnam Ltr FF5-16/03:gem 5750 Serial 0702, 17 Sept 1967, 4.

[vii] Ibid., River Patrol Force, 14.

[viii] Ibid., River Patrol Force, 15

[ix] Monthly Historical Supplement (May 1967), U.S. Naval Forces Vietnam, Chronology, vi.

[x] Ibid., Historical Supplement (June 1967), 11.

Author’s Note: Many thanks to Larry Weatherall and David Wilkinson for their help with this post.

[i] “Boy’s Harelip Corrected Through Navymen’s Help, Jackstaff, Naval Forces Vietnam, May 19, 1967, 4, which shows a photograph of Lieutenant Charles D. Witt and the 14 year old boy whose deformity was completely corrected; “Navy Surgical Team,” Jackstaff, JOC Ted Jorgenson, Naval Forces Vietnam, June 30, 1967, 4; See Also COMNAVFORVN Ltr FF-5/03:gem, 5750, Serial 0603 of 9 August 1967, which reports the May 24th, 1967 death of Lieutenant Witt in an ambush and other matters to include Operational Tempo (OPTEMPO).

[ii] Interview with former Engineman Second Class James Lawrence “Larry” Weatherall, USN, at Joint Base Little Creek/Fort Story, November 9, 2021. Larry Weatherall has been instrumental in restoring the PBR on static display at Joint Base Little Creek/Fort Story.

[iii] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 91-3.

[iv] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 95-6.

[v] Ibid., War in the Shallows, 104-110.

[vi] Monthly Historical Supplement (June 1967), U.S. Naval Forces Vietnam Ltr FF5-16/03:gem 5750 Serial 0702, 17 Sept 1967, 4.

[vii] Ibid., River Patrol Force, 14.

[viii] Ibid., River Patrol Force, 15

[ix] Monthly Historical Supplement (May 1967), U.S. Naval Forces Vietnam, Chronology, vi.

[x] Ibid., Historical Supplement (June 1967), 11.

No comments:

Post a Comment