Reviewed by Lee Duckworth

HRNM Docent

Paul Stillwell’s biography of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee Jr. is a book 40 years in the making and finally published in 2021. It details the life of Lee and focuses on his leadership experiences in the Second World War. Lee’s early life is unremarkable, other than the fact that he was an expert marksman. This shooting ability figures prominently during his time at the US Naval Academy (1904-1908) and participation in the 1920 Olympics. After graduation, Lee had assignments to various ships, including a battleship, cruiser/receiving ship, gunboat on the Yangtze River Patrol, and submarine tender. Stateside, his earliest shore duty was with the Bureau of Ordnance and later with the Fleet Training Division of the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations, where he made his reputation as a gunnery and fire control systems expert.

The author cites numerous examples of Lee’s ship-handling and tactics abilities that further his career as a surface warfare officer. Interestingly, Lee never had command of a battleship but was commanding officer of two destroyers. Two additional tours in Washington, D.C., with the Fleet Training Division (OPNAV 22) solidified his position as a gunnery expert, and his pioneering efforts in development of a Combat Information Center (CIC) set the stage for the major portion of the book and his career: World War Two.

The author details Lee’s preparations and conduct in battle in the Pacific during his three years as “Battleship Commander” and highlights three decisive battle opportunities. At Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Lee was commander of a task force consisting of two battleships and four destroyers. The November 14-15, 1942, night battle was the first time his units had operated together, and Lee had no opportunity to publish a formal Operations Order, nor was there any common doctrine. U.S. Navy forces opened the battle and had the advantage of radar, but in short order the destroyers at the head of Lee’s column were out of action. The battleship USS South Dakota sustained significant damage and was also out of the fight. Through Lee’s perseverance, the Japanese battleship Kirishima was sunk and a few hours later the Japanese forces withdrew. Lee’s utilization of radar in this battle proved to be the deciding factor and the turning point in the six-month fight for Guadalcanal. He later received his third star and was assigned as Commander, Battleships Pacific Fleet, where he was responsible for fleet battleship doctrine and procedures.

The author details Lee’s preparations and conduct in battle in the Pacific during his three years as “Battleship Commander” and highlights three decisive battle opportunities. At Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Lee was commander of a task force consisting of two battleships and four destroyers. The November 14-15, 1942, night battle was the first time his units had operated together, and Lee had no opportunity to publish a formal Operations Order, nor was there any common doctrine. U.S. Navy forces opened the battle and had the advantage of radar, but in short order the destroyers at the head of Lee’s column were out of action. The battleship USS South Dakota sustained significant damage and was also out of the fight. Through Lee’s perseverance, the Japanese battleship Kirishima was sunk and a few hours later the Japanese forces withdrew. Lee’s utilization of radar in this battle proved to be the deciding factor and the turning point in the six-month fight for Guadalcanal. He later received his third star and was assigned as Commander, Battleships Pacific Fleet, where he was responsible for fleet battleship doctrine and procedures.

|

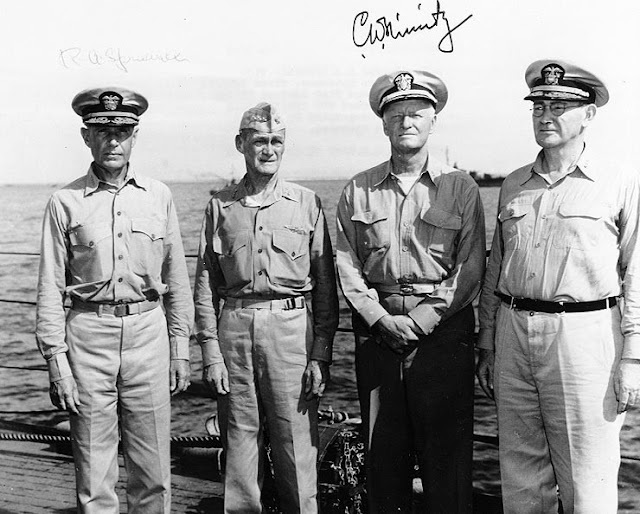

| ADM Raymond Spruance, VADM Marc Mitscher, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, and VADM Willis Lee in Feb 1945 (NHHC) |

|

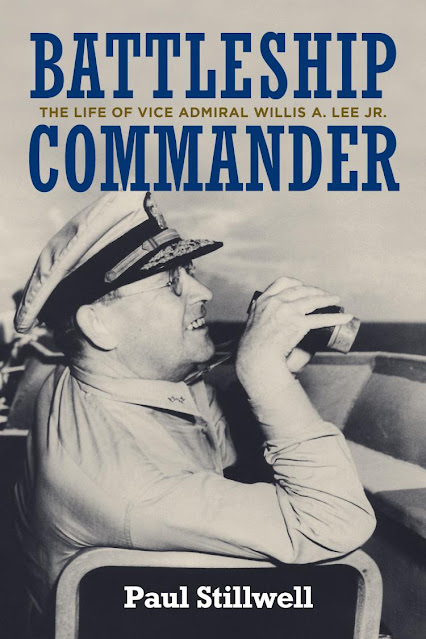

| VADM Lee in 1944 or 1945 (NHHC) |

|

| RADM Lee receiving the Navy Cross from Admiral Halsey after the Battle of Savo Island in 1942 (NHHC) |

No comments:

Post a Comment